Media

The Boring Internet

Is it just me, or did the internet become less exciting lately?

In the Summer of 2008, the internet suddenly became real. I was on a ferry crossing Lake Constance towards Germany for an extended camping weekend with people I’d never seen before in my life. All I knew about them was their voices. I was exhilarated and nervous.

They had one thing in common: They all played games in the same, what was then called «clan». The group was formed in 1999, mainly communicating via a forum and a TeamSpeak server. I joined in 2005.

It was a time before big social media platforms devoured our attention. In hindsight, a more innocent, wild, and naïve time as well.

But there I was, on this campsite, 17 years old and surrounded by people who suddenly became faces. It was a thrilling moment. I still am in regular contact with some of them. They became friends beyond gaming; we grew up together. Virtual sandbox buddies.

Today, forums and TeamSpeak have been crushed by Discord, messenger apps, and social media. The internet has crept into every crevice of our lives, yet it feels smaller and less exciting than ever.

Passive Consumption

Risking to sound like a boomer: I think the internet was a better place a decade ago.

It’s a bold claim, but here’s my argument: The algorithmic curation of any content makes everything boring eventually. There are two routes charted by the algorithms that end up at the ultimate boredom station.

First, let’s look at the user’s perspective. While algorithmic curation may improve the experience at first, it will finally lead to a state where you get more and more of the same. You might even enjoy that, but the joy you get from discovery fades fast.

To feel any kind of satisfaction or reward, you have to put a certain amount of effort into it. But algorithms relieve us of that effort, casually serving us what they think we might enjoy based on the past. And so we spend more and more time on these platforms to find the next big dopamine hit we’ll never achieve because we didn’t put in any effort.

It’s beneficial for the companies running these platforms but not so much for us.

The second perspective is the one from the creators. As algorithms dominate the distribution of content, creators have to bend themselves to their will (which is ultimately the will of the companies creating the algos).

So, to gain any kind of larger following, a monetisable audience, you have to play the game. Which means that more and more content seems the same. The most wonderful illustration of this phenomenon provides YouTube thumbnails.

Okay, admittedly, this sounds a bit too fatalistic, and plenty are out there creating unique things. Yet, when did you last open a social media platform and feel excited about anything you saw?

There was a time when Twitter and Facebook were my main sources of news and entertainment. I killed both accounts within the last twelve months. They felt neither social anymore nor did they provide any kind of value to my life. It became an ever more passive consumption than true interaction. (And in the case of Twitter, I couldn’t continue to support this out-of-control dumpster fire by a right-wing loon.) I don’t miss them one bit.

And as I feel rather similarly about Threads or Instagram, I try to cut time spent there to a minimum. Funny enough, it wasn’t a time limiter that helped to reduce my usage but simply deleting them from my phone’s homescreen. No temptation; prohibiting muscle memory to simply tap the icons.

No Pleasant Place

As I wrote in a previous newsletter, 2024, so far, has been a year of focus, reduction, or maybe even retreat to a selected few things.

I began supporting people on platforms like Patreon; entering smaller but real communities on Discord servers or WhatsApp groups where genuine interaction still occurs. I browse directly to websites instead of routing via social media. Sometimes, it even feels a bit like 2008 again.

But ultimately, I can’t stop feeling a slight disillusion with the state of the internet. Once I perceived it as a tool to connect with likeminded people and share ideas. And to some extent, it still is, but the dominating part today is passive consumption of algo-pleasing content, AI-generated bullshit, and advertising spam.

It’s neither a particularly interesting nor pleasant place to be.

Vapor Hypes

Despite all that, simply logging off is also not an option. Too intertwined is the internet already with our lives. But a more reflected, critical use might just be the right prescription—both individually and as a society.

Because if we’re honest: What’s left of the latest internet and technology hypes? Crypto? NFTs? Metaverse? Nothing really… And aside from useful niche applications like medicine, where’s the actual value of large language models in everyday lives?

Silicon Valley is frantically searching for the next big thing and failing. And just maybe, that’s not a bad thing if we collectively move away from this infested hyper-growth, «move fast and break things» mindset.

No Subsidies for Profit-Driven Publishers

Switzerland‘s news publishers demand further subsidies. It‘s a terrible idea. A rant.

It’s been two years since I said goodbye to my career in professional journalism. While the change wasn’t easy, settling into a new environment, I have zero regrets today.

A couple of days ago, I ran into a former colleague. When I asked how he was doing, he said, «You made the right decision…»

The media industry is in worse shape than ever. Multiple media outlets (legacy and digital) stumbled over toxic management and sexual harassment allegations. And, of course, there were layoffs.

The largest publisher, Tamedia (part of TX Group), announced it would cut 90 editorial jobs. Towards the audience, it laughably sold the cuts as «Setting the course for independent quality journalism».

Question: How big can the cognitive dissonance get?

Answer: Yes. But don’t worry; new lows will be coming.

Oh, and it’s worth noting that the TX Group continuously paid dividends to its shareholders: 65,7 million for 2023, for example. Stephanie Vonarburg, vice president of union Syndicom, states: «Over the past 15 years, the shareholders of the TX Group, owner of Tamedia, have siphoned off more than 670 million in dividends from a profit of 2.2 billion.»

Simultaneously, the publisher association «Verband Schweizer Medien» had the balls to call for expanded state subsidies.

Pardon my French, but: Are you fucking kidding me? Sorry, there will be more swearing.

We talk about the same publishers that first missed digitalisation, then bought back the digital marketplaces for an insane amount of money, cannibalised their products with free and cheap platforms, and cut costs on every corner to a degree where they have normalised a work environment with overtime, burnout, and abuse of power.

Without self-exploitation, the newspapers and online platforms would be half-empty.

We talk about the same publishers that for years attacked the publicly funded broadcaster SRG, undermining its justified status while crying «Free market! Free market!» and conveniently helping the far-right in launching political maneuvres against the institution.

Now, they beg for subsidies with one hand while the other lines the pockets of their millionaire and billionaire owners.

I feel sorry for the journalists who are still trapped in this system. Because they love their work. Because this job is without alternative for them.

And yes, some of them are still defending the publishers, blind to the fact that they don’t give a fuck about journalism and its vital function. It’s all about the bottom line, the profit, the bonuses. Numbers before people.

I’m all for a robust subsidy scheme for journalism. Especially a start-up fund to give some leeway for new ideas and brands. Unfortunately, we’re years away from finding a solution.

But dumping money in this rotten conglomerate of few publishers is by far the worst way. No subsidies for for-profit media organisations. Plain and simple.

Okay, what can we do in the meantime? Support the hell out of new media companies, especially local ones like «Hauptstadt» or «Tsüri». There, you know that your money is ending up in journalism.

Twitter Postmortem: Or A Slow Goodbye From Big Social Media

I feel exhausted by social media.

I deleted my Twitter account after 12 years—and it felt great.

Twitter has been an essential gateway for me into journalism. I remember that back in the day, it used to be a common thing to network: «Hey, I'm Janosch, we follow each other.» The platform has also been a reliable news feed, carefully curated by following established journalists and sources from around the globe.

But no more.

While Elon Musk continues displaying examples of terrible leadership, peddling conspiracy theories, and enabling more and more extremist views and hate speech, it's time to leave. There's less value found on this platform, now called X, after the worst rebranding in recent history, and therefore even fewer reasons to justify staying.

Deleting my Twitter account prompted me to reflect on my relationship and history with social media platforms. Broadly, I can identify three distinct stages.

Stage I – Experiments

It started in the messy days of the internet with decoupled experiences from Habbo Hotel and MSN Messenger to gaming-related apps like Xfire, TeamSpeak, and forums. The first service I used resembling today's platforms was Netlog, soon consumed by the growing giant Facebook.

Those years, probably the first decade of the 21st century, were exciting. Driven by curiosity and definitely a healthy portion of naïvety, I dove into every possible network.

Data security concerns? Just didn't exist. Oversharing? Constantly.

Stage II – Purpose

Later, as a young journalist, social media platforms played a significant role. They were a necessary tool for sourcing and telling stories.

My accounts mostly became professional tools rather than personal spaces, and for the most part, I curated content carefully. They also became more of a broadcasting channel than a place for discussion.

Stage III – Exhaustion

Fast-forward a couple of years to 2023. My circumstances have changed: No longer working in the media industry, the big social media platforms are no longer necessary to thrive.

And I feel exhausted.

My Facebook feed is a neverending stream of stupid jokes, and LinkedIn's algorithm boosts fake hustle gurus. Today, I hardly find any joy in Instagram anymore. I mostly use it to send silly Reels to a handful of friends and post for my music blog, Negative White.

Mastodon, where I had an account since 2016, isn't my cup of tea. I deleted TikTok and BeReal again.

Just YouTube has always been a constant; however, it's not a social experience to me but an entertainment and learning platform. And now, with Twitter done and dusted, maybe Bluesky will create a new news feed for me.

What defines a social media experience? Is it simply the digital extension of an analogue relationship or the random connection with strangers?

For a long time, there was this fear of missing out. You know the drill: You're missing out if you're not on Facebook. If you're not on Instagram, you're missing out.

Today, I hardly find any clear value in social media platforms. Using them gets more and more exhausting and too time-consuming for little reward. Did they change, or did I?

My digital social life has mostly returned to where it started: A handful of group chats on different messengers and a few Slack and Discord servers.

Charlie Warzel wrote it best in «The Atlantic»:

The internet has never felt more dense, yet there seem to be fewer reliable avenues to find a signal in all the noise. One-stop information destinations such as Facebook or Twitter are a thing of the past. The global town square—once the aspirational destination that social media platforms would offer to all of us—lies in ruins, its architecture choked by the vines and tangled vegetation of a wild informational jungle. This may be for the best in the long run, although the immediate effect for those of us still glued to these ailing platforms is one of complete chaos.

Trigger Warnings Don‘t Work: Should The News Stop Using Them?

A recent meta-analysis looked at the research around trigger warnings. The conclusion: They don't work.

This post contains information that might disturb you.

Trigger and content warnings like the one above have become more frequent in the last few years. Regarded by many as an effective tool to prevent people with traumata from reliving their pain and anxieties, they indeed seem well-intended.

But here's the problem: Trigger warnings don't work.

I recently stumbled over this meta-analysis that collected the findings of several studies on the effectiveness of trigger and content warnings. The research's findings are surprising:

This meta-analytic review suggests that trigger warnings–statements that alert viewers to material containing distressing themes related to past experiences–do not help people to: reduce the negative emotions felt when viewing material, avoid potentially distressing material, or improve the learning/understanding of that material.

However, trigger warnings make people feel anxious prior to viewing material. Overall, results suggest that trigger warnings in their current form are not beneficial, and may instead lead to a risk of emotional harm.

Phew, that's some news.

Categorising Contexts

There are different kinds of settings and types of warnings that could (maybe should) be distinguished. Philip N. Cohen, a sociologist at the University of Maryland, suggests the following categories on his blog:

- Warnings of content likely to be disturbing to many people in the audience.

- Warnings of content that may trigger post-traumatic stress responses.

- Warnings of obnoxious, offensive, disagreeable, or dangerous ideas.

Cohen also recommends on when to use warnings, and it's only the first category. In cases of violent imagery, for example, he thinks that "in these cases, a warning of the impending discourse is something like common courtesy."

Nevertheless, Cohen also nuances his suggestion as there are settings where content warnings seem optional:

A horror film can be expected to surprise you with specific acts of violence, but you know something bad is coming; a sociology class on racial inequality should be expected to include discussions of lynching, a history documentary on war is expected to show people being killed.

What About The News Media?

In line with Philip N. Cohen's argument, the news is a context where sensitive topics occur. In my years as a journalist, I've experienced many debates around content warnings and notes. In every job, there has been at least one discussion about whether we can show specific graphic images or not.

Especially cautiously treated, for example, are reports about suicide. In the rare cases when reporting is done, the stories are accompanied by a textbox that provides information about organisations that offer help.

These media ethics discussions are essential and should be held more publicly rather than contained in the newsrooms. The Swiss Press Council has many directives that specifically address war, crimes, and suicide reporting.

Despite all existing guardrails, the meta-analysis' findings lead to the simple question:

Should The News Get Rid Of Trigger Warnings?

First, we have to cover some basics.

On one side, you could argue that reality isn't all rainbows and unicorns. The media has to report accurately, and violence, death, crime, and war are a part of it.

Moreover, shocking images can trigger political or societal action and raise awareness drastically. Here, the photos of refugee boy Alan Kurdi and, more recently, images from the war in Ukraine come to mind.

The GuardianHelena Smith

The GuardianHelena Smith

On the other side, news media also have to report responsibly. They are responsible for protecting the dignity of the people depicted and their audiences, at least to a certain point. Simply publishing graphic content for the spectacle's sake is blatant sensationalism.

"We are evolutionarily wired to screen for and anticipate danger, which is why keeping our fingers on the pulse of bad news may trick us into feeling more prepared."

However, Ahrends adds that the feelings of fear, sadness, and anger triggered by negative headlines can keep people stuck in a "pattern of frequent monitoring," leading to worse moods and more anxious scrolling—also dubbed "doomscrolling".

However, as the research suggests, placing a trigger warning in front of a story about rape or domestic violence doesn't prevent victims from reliving their horrible experiences.

And putting content warnings or blurring graphic images often seems like a fig leave to avoid the necessary debate around what news should and shouldn't show.

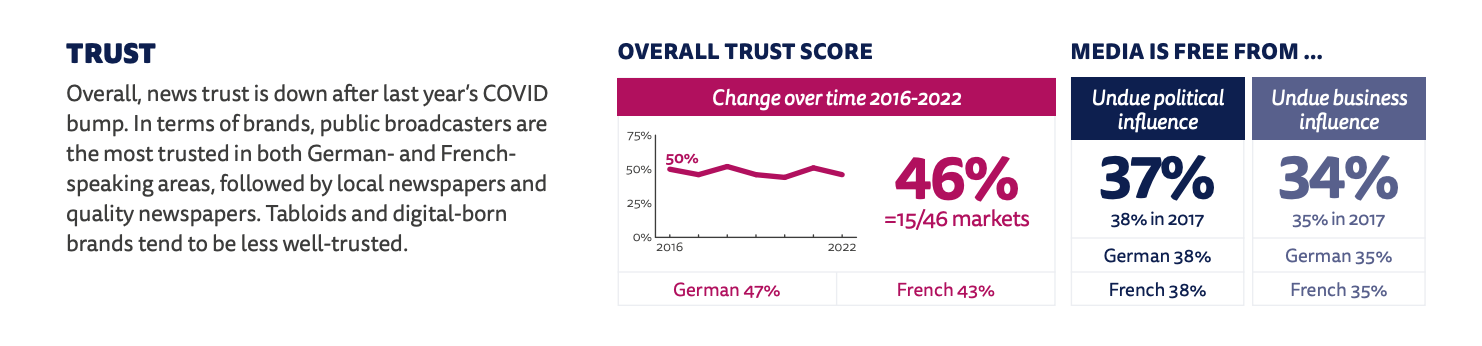

It also remains true that more and more people avoid the news entirely because of its negativity. They feel that, as described in the side note above, it impacts their mental well-being. They avoid the context that might trigger anxiety and distress, which can be interpreted as responsible behaviour. The Digital News Report 2022 found:

The proportion of news consumers who say they avoid news, often or sometimes, has increased sharply across countries. This type of selective avoidance has doubled in both Brazil (54%) and the UK (46%) over the last five years, with many respondents saying news has a negative effect on their mood.

But if people avoid journalism because of its negativity, it cannot provide its societal function of informing the people and enabling democratic discourse. So yes, the news should probably get rid of trigger warnings. First, however, newsrooms need solutions to create an environment that people aren't avoiding.

Alternative offerings like the photo-free reporting on the war in Ukraine by Swiss news website "Watson" could be a possible step.

Let me know your thoughts in a comment below or reply to the email.

3 Things That Should Be Addressed By Media Companies

A toxic environment leads to high turnover and mental health issues. Organisations that care about their bottom line should address the causes.

I'm not a vengeful or resentful person. However, my last post explaining why I left the media industry focused heavily on negative aspects. The post is now also available in German.

Naturally, I was slightly anxious the night before publication. What reactions will I receive—approval or rejection? Will I start a shitstorm? Or, even worse, no reaction at all?

Despite receiving some dismissive comments, my fears weren't justified. I've received many messages from Switzerland and Germany in the last few days. There were reporters, media managers, editors, and people who also left journalism.

Their messages confirm: The media industry has a leadership and culture problem.

The Great Resignation Accelerates

The media industry isn't by all means alone. The so-called Great Resignation has been looming in the Western hemisphere for months. Fuelled by the Covid-19 pandemic, where people were forced to quit their jobs or have time to reflect, many found that their current work environment didn't satisfy them anymore. And with remote work, new possibilities opened up.

The signs of a shift in employee mindset are also evident in Switzerland. Airlines have trouble finding personnel, restaurants struggle to attract employees, and even teachers are scarce. Lately, seven doctors quit their jobs at a hospital in Einsiedeln [all articles in German].

However, there's still no debate about the Great Resignation in Switzerland. Instead, it's called "Fachkräftemangel"—skills shortage. Of course, for some professions, this is a problem. But at the same time, the question of whether there's an issue with working conditions is rarely asked. So, I guess that the Great Resignation will get more severe in Switzerland.

Like any other industry, media companies should rather sooner than later address the topic—both as a driver of public debate and in their organisations. On a systemic level, the loss of journalists harms a functioning democracy, and it's problematic yet understandable that many journalists switch to public relations and corporate communications.

Toxic Culture Impacts The Bottom Line

A toxic workplace is one of the biggest drivers of why people quit their jobs. "In today's competitive labour market, one of the leading reasons for high turnover is the emergence of a toxic atmosphere at work. Employees often leave bad workplace cultures in search of healthier environments, where they may feel more fulfilled on the job," writes The Society of Human Resources Management (SHRM).

There are five prevalent signs of a toxic culture in companies:

Why I Left The Media Industry After 10 Years

Since I was 15, I have wanted to become a journalist. Now, I say farewell to journalism, the industry that provided great experiences but also a lot of frustration.

Prologue

For years, if anyone asked me whether I could picture myself doing anything other than journalism, I categorically denied it.

Despite knowing that the media industry was a stressful environment undergoing a disruptive change, I still was intrigued by this industry in disruptive change. I wanted to become a part of that change and help shape the future of journalism.

However, after about a decade, I had enough. And although I had incredible opportunities, unforgettable moments, and great colleagues in every single company I worked for, the following post focuses on the negative that drove me out of the industry.

It's a highly subjective, personal, and biased account. Maybe a small reckoning.

Part I: Exciting Beginnings

My career as a journalist began as classic as possible. Never knowing what I should become, I signed up as a reporter for the school's newspaper because I had always had a passion for writing and storytelling. Then, it suddenly dawned on me that journalism is an actual job. I've found my calling.

But I was a lazy teenager and dropped out of school, starting an apprenticeship in 2009. Nevertheless, I had my goal and was eager to get a foot in the door. I started writing short band biographies for a concert photographer and freelanced for some webzines and a local paper. In 2010, I founded my magazine, Negative White, together with my brother, who had just bought his first camera.

These early years were shaped by curiosity, the excitement of the unknown, many mistakes and learning by doing. Most of the time, I didn't know what I was doing. But I had fun and could follow my passion. My magazine grew an audience and other volunteers. Two years in, I even had the opportunity to interview Sir Paul McCartney.

I became a member of the young media association, now called Junge Journalistinnen und Journalisten Schweiz (JJS), and began to grow my network. In 2013, I started studying journalism and communication. As part of the curriculum, I gained my first experience in editorial offices at the Swiss national broadcaster SRF and a local paper.

Part II: First Cracks

The internship at SRF was a wild ride with a committed team. I was never really interested in television, but I learned to love video content. And although I would stay at the news bulletin 10vor10 at the desk, the first cracks in my journalism dream started to show.

In hindsight, I had terrible tasks as an intern. It was the peak of ISIS, and I had to plough a whole day through propaganda material. Eight hours of beheadings, mass executions, and other glorified violence.

Working at the desk after the internship has been a thrill. Being part of live broadcast productions is an adrenaline-spilling affair. As a desk employee, I was the right hand of the producers, fact-checking, establishing connections to the correspondents, ensuring the correct timings of the lower thirds, writing online texts, and more—a great responsibility.

However, there was a lot of fluctuation in the team, which directly impacted the programme's quality. Often, the people at the desk were students, aspiring journalists who wanted to gain storytelling experience that they couldn't get at the job. So I drafted a proposal for the editor to allow us to create two stories a year. He declined and said: "This is a support job, and it will forever be one."

My encounter with the editor was the first that embodied an outdated management style characterised by a refusal to change, holding on to power, and sometimes unsettling behaviour.

As an online journalist, I still struggled with an older editor who told me we should do "more with boobs" online to boost clicks.

At the interview for my next job at another local paper, the editor-in-chief asked me about my political affiliation. After I dodged the question several times, he said: "If you had to choose to become a member of a political party or get stoned, which party would it be?" – I said: "I choose the stoning."

After being a journalist for a couple of years, I was less and less interested in writing about things I didn't really care about. I fully knew what I was getting into when I chose journalism as a career. It's a stressful job that makes it incredibly hard to have a proper work-life balance. Most companies don't have actual—and, by the way, legally required—time reporting. Instead, the system merely puts in standard daily hours to comply without accurately representing the work done. But many journalists I know have easily 100 hours of overtime.

The job also got more complex, requires more skills, but isn't that well-paid nor a highly regarded profession nowadays. Journalists used to have just one thing to do: tell the story. Today, you're expected to take photos, shoot videos, and post on social media.

In many regards, I've always been fascinated by these new facets. I saw it as an opportunity to learn new skills and maybe discover new areas I could excel. But there's no way around it: A lot of additional work is put onto journalists because fewer people are working in newsrooms.

However, I still felt that the media industry was an exciting field despite its dire situation with declining revenue. That's why I joined Blick, first as a Project Manager in the newsroom, later as Head of Community, and then as Product Owner. I hoped that switching to a more background position would keep me happy for a long time.

Part III: Only Management, No Leadership

"It's not a shitty job; it's the shitty conditions and perspectives," said Simon Schaffer of JJS recently. It's a brutally honest and accurate statement.

Especially freelance journalists are at the very bottom of the food chain: Karin Wenger, a friend and a freelance reporter covering the Middle East, tells me that she has to use a lot of her ever-smaller salary to cover travel expenses as most of the newsrooms scraped the budgets for things like travel and translators long time ago. It's madness.

I've written about mental health problems in the media industry before. However, I again experienced first-hand and by many accounts in the last few months how devastating the lack of leadership can be to people. I know many journalists who had burnout at around 30 [German] and had to get professional help. Or they even began abusing alcohol [German].

I regularly talk to talented reporters who feel similar: Yes, journalism is their calling. And yet, only a couple of years in, most of them are thinking about changing careers.

But who is ultimately responsible for working conditions that seem to make people sick or drive them out of their beloved field?

The management. And yes, I specifically use the term 'management' because there's a lack of true leadership in media companies. It's the main reason why I leave the media industry now.

I won't go into detail about my experiences in various companies. It's not about individuals or instances but a more systemic issue. A synthesis of my own accounts and those of friends or students at MAZ, where I used to teach, paint a clear picture: It all boils down to a lack of trust in the employees and a missing vision and strategy to align efforts.

- Safety over experimentation.

- Stop doing is rarely a sincere option.

- Great ideas get watered down through endless discussions.

- No strategic approach to 'shiny new things' like TikTok.

- Work done by internal teams gets challenged by expensive external agencies.

- Reports are created for accountability rather than an opportunity to learn.

- Expertise is less important than gut feeling.

At some points, I was amidst internal political struggles and personal agendas, but I had no interest in participating. It's wasting time and energy.

Leadership should provide an environment that empowers people and allows them to be at their natural best. And if a company hires, for example, an UI/UX designer, you should probably listen to their advice. Otherwise, why did you hire them in the first place? However, from my experience and what I regularly hear from friends and colleagues, micro-management is prevalent.

I fully recognise that the media industry is in a dire situation. Revenue is shrinking, and although alternative business models exist, there's no one-size-fits-all solution. The broader media and information landscape has constantly been disrupted for decades by new technologies and platforms. Change is a constant, requiring a new kind of leadership mindset, organisational structure, and corporate culture. But frankly, media companies are still managed like 30 years ago.

The declining trust in journalistic work is a fundamental challenge for the industry. And I began to realise that if an organisation cannot create that trust within itself, it's probably futile to build it towards the institution.

Epilogue

After only a bit more than four years, I decided to leave Blick. I was disillusioned, frustrated by the media industry, and physically and psychically exhausted. In the mornings, I was almost unable to get out of bed. I didn't feel any joy because I couldn't do my job properly. I felt an impending burnout.

I was done fighting, especially after having already spent a lot of energy to get recognised with the Community team I helped build. Despite working alongside hugely talented and committed people, I felt that I couldn't give enough anymore that I was satisfied with myself. It's a sad realisation, yet it also gave me a weird sense of calmness.

With just three bigger media companies left (two of them I've already experienced), I only wanted to get out of the industry I worked hard to get into years ago. And I'm glad I'm out because it began eroding my passion for writing and journalism.

Employee retention is another challenge closely connected to the company culture and trust. It gets harder and harder to find interns, and a quick check of medienjobs.ch reveals that attractive offerings remain open for months. When looking for my first full-time job, I hardly saw any open positions.

Last year, every week, a journalist left the field in Switzerland. The media magazine persoenlich.com is running a series of interviews with former journalists. So it should be an eery wake-up call for all brands and the industry that there's a problem. Simon Sinek said it perfectly:

"The Great Resignation is an indictment on decades of substandard corporate culture and poor leadership."

Being a journalist has been and will always be an exciting profession. But today's ecosystem is failing the people and employees. Maybe these big legacy brands need to vanish and make space for something new if they're unwilling to fundamentally change how they do business. I certainly will miss journalism but not the system that produces it today.

The Metaworse

Let's take a look beyond the marketing hype.

I've been creating digital avatars for the better part of my life. It was probably not the first one, but the one I clearly remember: my alter ego in the MMO Guild Wars around 2005. Later for Star Wars Galaxies and Star Citizen.

Being fascinated by the immersive nature of games, I fully understand the notion of re-creating oneself in a digital world, joining people from around the world and going on adventures.

For me, born in 1990, the internet and digital spaces have been a welcome escape from Switzerland's conservative and boring countryside. And some of my oldest friendships trace back to those intense gaming times, although they trickled into "real life" now.

I also strolled around in Second Life for those who can remember the first actual attempt to re-create the world in the digital realm. However, when I tried the simulation, the initial hype had already passed, and the concept didn't capture my mind. The main problem: Second Life was like real life. Everything cost "Linden dollars", which could be purchased for actual dollars, diluting my escapist desire.

In 2015, I first put on a VR headset. It was an Oculus Rift Development Kit II, even before the company formerly known as Facebook bought the enterprise.

Since then, VR technology has come far. First, the resolution and general experience improved to make virtual reality access consumer-ready. Combined with the astonishing progress in video game graphics, a second attempt at creating a metaverse seems inevitable.

Given my previous gaming experience and general affinity for technology, I should be excited about the current efforts around the metaverse. But I'm not.

What Is The Idea Behind The Metaverse?

"The metaverse is defined as a unified 3D virtual world where users can conglomerate via their digital selves (i.e., avatars) and perform complex interactions," writes XR Today. It's pretty vague, to say the least.

But the hype is real. Billions are invested in creating the technological foundation for the metaverse. Most famously, Facebook announced its move with a silly rebrand into Meta. But also Epic Games (the makers of Fortnite and the Unreal Engine), Chinese tech giant Tencent, Microsoft, and even Apple are working on it.

Despite its vague definition, I have little doubt that the companies involved in building the metaverse have the financial resources and technological capabilities to create an excellent experience.

Fragmented Domains

Meta's CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, stated in his manifesto: "When you buy something or create something, your items will be useful in a lot of contexts, and you're not going to be locked into one world or platform."

Public perception of the metaverse is precisely that: People and companies pouring metric tons of marketing money into the idea are expecting a single platform. And Meta repeatedly said that no single company would own the metaverse.

I call bullshit.

Culture of Speed

Why the culture of speed makes it hard for newsrooms to embrace a product mindset.

The business of news is fast-paced. New information surfaces faster than ever before; bulletins, press releases, and tweets drop in by the second. For the past years, newsrooms had to adapt to process the ever-faster spinning news cycles, verifying and curating the most important and relevant information for their audiences.

The traditional deadline approach from print times has been largely abandoned in the digital publishing realm. Instead, stories get published throughout the day to meet the demand. Then, journalists move on quickly to a follow-up or even a new story.

The increased pace creates many challenges around journalism itself worth exploring. However, this culture of speed established in newsrooms also makes it difficult for media organisations to embrace the transformation to a product-focused mindset fully.

Agility On Steroids

People working in product management—including myself—tend to complain about the newsroom's lack of understanding of agile development. There are undoubtedly true aspects to this.

Usually, a story is refined until published; changes occur rather occasionally than institutionalised. The journalists' strive to perfection, paired with a still roaming deadline socialisation, is fundamentally different from an iterative approach to product development.

But the more I think about it, the less confident I am in this theory that a lack of knowledge is why news organisations struggle with a product mindset. There are two key reasons:

- The production of journalism is in itself an agile process. Like any product, stories go through discovery (research, investigation) and delivery (writing, production) phases. Each draft is a prototype that is being re-iterated based on new information and feedback.

- Newsrooms are masters in agility. No organisation outside of journalism can react as quickly to new developments as newsrooms. In case of breaking news, priorities are shifted dramatically in a matter of minutes. Everyone that has experienced a breaking news situation for the first time is stunned by the impressive adaption rate.

Basically, newsrooms live agility on steroids. They move as fast as the news cycle requires.

Note

This observation is only valid for highly digital, news-driven organisations. Local newspapers still relying heavily on print indeed struggle with agility, while more magazine-like online publications have a much slower pace.

Understanding Cultural Differences

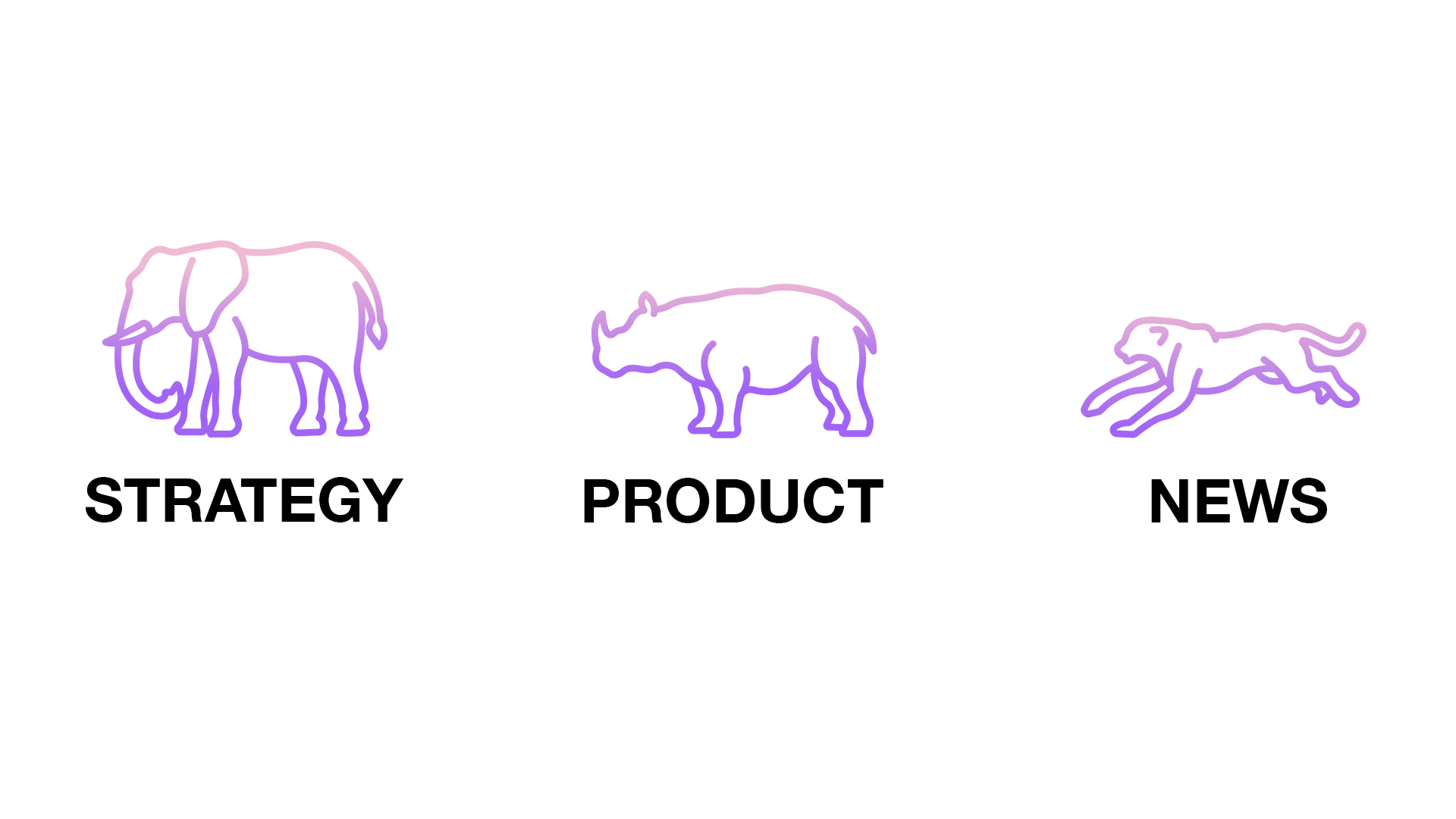

If we leave assumptions and biases aside, we can assess that both the newsroom and the product development work agilely—the main difference is the speed. Additionally, every organisation has a third gear that moves even slower: Strategy. It's even more complex to translate to everyday work in a newsroom than product development; strategy plays hardly any role in deciding which stories to write. On the other hand, strategy is a massive factor in a product roadmap.

Update

Of course, strategy plays a significant role in the editorial direction of a news organisation. However, in journalists' daily work, it isn't as prevalent as it is for product management.

Nevertheless, understanding that the newsroom and product development basically work with the same principles but at different speeds is crucial. It creates a common ground for communication and education, which drive culture change.

As a product manager in a media organisation, it is essential to be aware of the culture of speed inside the newsroom. Furthermore, he has to thoroughly understand how the journalists work on their part of the product. These two factors heavily influence the interactions between newsroom and product to happen.

The culture of speed often leads to exaggerated expectations. "We need feature X now!" or "Why does feature Y take so long?" are phrases you‘ll often come by in discussions with newsroom staff. The constant urgency is deeply engrained into journalists' mindsets and drives their behaviour in every interaction. As a journalist turned product manager, I still feel this need for speed.

Attach Communication To Familiarity

If a product manager has no or little knowledge of the cultural background of these phrases, it gets difficult to find satisfying answers. So, an effective way is to find familiarity in comparisons between journalism and development.

Here are some examples:

- Product development is like investigative reporting. You need time and teamwork to get to the bottom of the user story.

- The roadmap is like an editorial publication schedule. Priorities can change like news cycles, but they usually shift not so fast.

- User-centred development is like optimising a headline. We want to deliver a product that captivates the audiences and keeps them engaged.

You can develop many other comparisons to create a common language and start educating effectively.

Don't Neglect The Differences Either

Naturally, it is not the solution to bridge every difference. Communicating that the differences aren't as big isn't enough. Education still needs to take place.

Product development has more constraints and stakeholders that need consideration, whereas journalists (in an ideal world) only are bound by their principles and only answer to the audience.

Furthermore, product iterations usually have larger leverage and more considerable risk. In comparison, the newsroom speeds through dozens, even hundreds of iterations with every published story, the individual article itself has a much lower impact. Suppose it performs well, great! If it doesn't, it's soon forgotten. There's no lasting impact on the product.

Note

Obviously, journalism can have a great impact on society and policy or the product and brand perception. While an individual story may trigger an impact on the first two, it's far more unlikely that a single story changes how the product or brand is perceived.

However, if there's a product change, it may instantly impact everything—from the user experience to advertising performance. And these changes cannot easily be reverted like a typo in a text. Research, consideration, and alignment must be thorough as the danger of significant impact loom above every feature change. It takes more time.

Best Of Both Worlds

Now, both the immense speed of the newsroom and the slower tempo of product development have their righteous existence. They're needed to create success in their respective fields, and pitting one speed against the other isn't a good idea.

However, to see progress within the shift to a product-driven organisation, we have to think about how we can bring both worlds together and even learn from each other. The questions around effective collaboration can be:

- What can product managers learn from the speed of the newsroom? And vice versa?

- What strategic goals can be translated to product and editorial to enable a department-spanning collaboration?

- Which opportunities provide the best area to grow from each other's strengths?

Ultimately, only joint forces between all departments in the organisation leads to an effective transformation process.