Last week, I began studying Digital Management at Hyper Island. The first couple of campus days were emotionally challenging, inspiring, and enlightening. Here’s my biggest takeaway so far.

My motivation changed quite drastically throughout the months before the course even began. When I applied, I worked as a project manager. So naturally, I hoped to learn more about tools that will help me in that area.

Then, I got the position as the leader of the newly founded community team. I hoped, the master’s degree will provide me with skills and frameworks to lead.

But when I spoke to several Swiss alumni, I realized that it would probably change me instead of just stitching some knowledge onto me.

And that’s what happened. The so-called Foundation Days at Hyper Island kickstarted something in me, that was sound asleep for a far too long time: an inner dialogue about my feelings and needs.

While reflecting on the experience made in Manchester, I also came to another realization: You can’t form relationships with positions–only people. You may have respect because higher positions have higher authority. But that doesn’t mean you’ll connect on a human level.

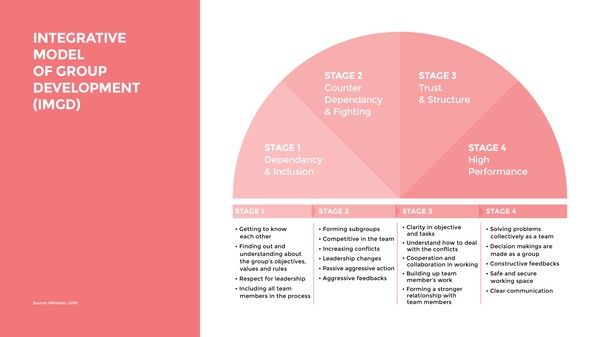

In this rapidly changing world of digitalization, we’re facing more and more complex tasks. Effective teamwork is essential. I can recommend the book “Creating effective teams” by Susan A. Wheelan. It’s a great guide to understanding how groups have different stages in their lifespan. Here’s an article that may help you either.

Relationships formed between group members as well as the leader are crucial to creating a trusting, open, and creative environment that drives innovation.

Leaders have to inspire the change towards a more emotional – in fact, human – culture. That means they have to take the first step into vulnerability as described by Brené Brown:

Wannabe-Innovative Leaders

Media executives like to talk about innovation but lack the will to change their management style.

This week, I received another issue of Anita Zielina’s ‘Notes on Change,’ titled “Why I Moved to NYC to Train Innovative Media Leaders.” You should definitely subscribe to this newsletter.

Anyway, Zielina worked for about ten years in the media business. She tells what she loved about the jobs. And what she didn’t like:

The lack of creative space and lack of appreciation for innovation. The millions of meetings. Petty political fights on the management level. But, more than anything, my share of bad leaders I encountered, followed by disbelief when they still got rewarded with additional responsibilities by boards or CEOs.

Ultimately, she asks the crucial question:

What if it is not the new product, […] that will ‘save’ the media industry/the news organization in question, but if it’s rather our culture that is holding us back, and that will, ultimately, kill us if we don’t radically transform?

I would argue, she’s right.

Now, Zielina mentions the lack of appreciation for innovation. Here’s where I don’t entirely agree with her. At least in Switzerland, many media executives talk about change and are looking for new products and services. And, so I think, are also showing appreciation, if there’s any innovation happening within the company.

Don't ask stupid questions

Why trust is the key ingredient to having quality user feedback.

“Everybody lies” is a New York Times bestseller, proposing that social science approaches are basically worthless. Some arguments may even strengthen the theory by author Seth Stephens-Davidowitz. For example, people won’t always tell the truth because the answer contradicts social desirability.

Journalism is no stranger to this behaviour. Surveys often conclude that the audience wants longer, in-depth reporting while data shows otherwise. Of course, you’ve to read those surveys always with a grain of salt.

However, is data the “truth serum” Stephens-Davidowitz claims it to be? When it comes to design improvements, it’s probably a viable solution to observe how people use a product rather than to ask actively to avoid a distorted image. This process results in constant iterations of improving and testing. That’s a perfectly fine use of data.

Now, I see two significant pitfalls with the sole reliance on data. First and most obvious: Data is also subject to confirmation bias as soon as it gets analyzed by someone.

Kill The Teams

What a clickbait headline! But let me explain why newsrooms need to imagine a new form of collaboration.

Our world is changing more rapidly. Globalization and digitalization haven’t just made humanity more connected than ever but also added a unique complexity. It’s hard to understand the interconnected and interdependent issues we face as a society.

Journalists are no exception. However, newsrooms still try to tackle modern-day challenges of informing the public in old-fashioned settings.

These damn silos

The main problem with newsrooms is silos: Most of the newsrooms work in outdated teams that evolved in an era when the world seemed more straightforward. That’s why we have desks for politics, economics, culture, sports, et cetera. For a long time, these teams were a useful tool to report and manage talent. And to some extent, they still are. It’s essential to have these expert hubs because they cultivate sources and experience.

But if we are forced to report on complex issues, the probability is high that it doesn’t touch just one aspect of our society. At large, newsrooms don’t seem to acknowledge this challenge on an organizational level.

I can only speculate about the reasons. I think that often false incentives and a grip on power may contribute to the consolidation of the status quo. By false incentives, I mean the comparison of key metrics in a competitive sense. We’ve all heard it: “Politics performed better than economics. Step up your game, economic reporters!” This competitive environment nurtures silos and hinders much-needed collaboration. Every team is just looking for itself because the analytics cannot deliver decent numbers on interdisciplinary effort.

What is the result?

Readers get fragmented reporting on all the issues, making it harder for them to understand the implications in a holistic way. One day, politics writes about Facebook, the other day, it’s economics. And a week later, we hear something from the tech reporter.

Why We Should Care About Facebook's Behaviour

How do we, as a society, respond to the ethical questions Facebook is asking?

How do we, as a society, respond to the ethical questions Facebook is asking?

A few weeks ago, Chris Hughes, one of Facebook’s co-founders, published an opinion piece in The New York Times, proposing to break up the organization, that holds the keys to Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp. Facebook, and especially CEO Mark Zuckerberg, has gained power beyond what’s right for the world, says Hughes.

The article rose a lot of attention, but I didn’t think more about the subject until today. I had a brief discussion about it on Twitter. The other person stated, he doubts the monopoly of Facebook and the dangers and damages it imposes on society. In short: The government should not break up the Facebook complex, the person wrote. There were a lot of alternatives to the big blue’s services from traditional text messages to rising stars like TikTok.

A different internet experience

At that exact moment, it occurred to me: This statement is dripping with western privilege. I grew up with message boards, blogs, forums, chat services, TeamSpeak, and independent websites. We experienced a free and diverse Web 2.0.

My canvas for prioritizing and organizing my resources.

In 2007, I finally knew what I’d wanted to do for a living. It was the school’s newspaper that led me to become a journalist – no matter what.

During my apprenticeship, I started an online magazine called Negative White, covering alternative music and culture. That was almost a decade ago. It was a hobby back then but evolved to voluntary work over the last couple of years. The team grew, additional products and services were added. It was a hell of a ride. Negative White was my playground, a lab for experiments. The experience gained is invaluable.

However, I’ve achieved my initial goal to work full-time in journalism. And it gets harder to find energy and time getting stuff done for Negative White. That puts me in a quagmire: As a leader, I failed to hand over control. I became too big to fail, which was also crucial for the project’s success or descent. Maybe that’s the most important lesson I learned.

Now, I’ve to face tough decisions: Do I keep on struggling or do I quit? Are there any means to reduce the workload of about one to two hours per day by delegating tasks or stopping certain services? I don’t have the answers yet.

Being at your best

Ultimately, I’m convinced that we can only be at our best when we focus on a few things. You simply cannot commit yourself to ten jobs as good as to two. Admitting your limits is hard, especially if it involves a passion project like Negative White. It is a painful process that will pay off eventually in furthering the personal perspective.

Even if I decide to stop the project by the end of the year, it won’t be a failure after all. It was never meant to be as big as it is now, nor a lifelong engagement. It just grew organically.

Three key metrics

Nevertheless, I’m in a completely different place now than ten years ago, facing a new wave of having to prioritize and organize my resources. I have a small canvas of doing precisely that, but it requires total honesty.

Everything I do needs to check two of these three boxes:

Joy

Do I enjoy the work that I’m doing? That doesn’t mean I’ve to be happy all the time, but the overall feeling should be some sort of fulfillment.