3 Things That Should Be Addressed By Media Companies

A toxic environment leads to high turnover and mental health issues. Organisations that care about their bottom line should address the causes.

I'm not a vengeful or resentful person. However, my last post explaining why I left the media industry focused heavily on negative aspects. The post is now also available in German.

Naturally, I was slightly anxious the night before publication. What reactions will I receive—approval or rejection? Will I start a shitstorm? Or, even worse, no reaction at all?

Despite receiving some dismissive comments, my fears weren't justified. I've received many messages from Switzerland and Germany in the last few days. There were reporters, media managers, editors, and people who also left journalism.

Their messages confirm: The media industry has a leadership and culture problem.

The Great Resignation Accelerates

The media industry isn't by all means alone. The so-called Great Resignation has been looming in the Western hemisphere for months. Fuelled by the Covid-19 pandemic, where people were forced to quit their jobs or have time to reflect, many found that their current work environment didn't satisfy them anymore. And with remote work, new possibilities opened up.

The signs of a shift in employee mindset are also evident in Switzerland. Airlines have trouble finding personnel, restaurants struggle to attract employees, and even teachers are scarce. Lately, seven doctors quit their jobs at a hospital in Einsiedeln [all articles in German].

However, there's still no debate about the Great Resignation in Switzerland. Instead, it's called "Fachkräftemangel"—skills shortage. Of course, for some professions, this is a problem. But at the same time, the question of whether there's an issue with working conditions is rarely asked. So, I guess that the Great Resignation will get more severe in Switzerland.

Like any other industry, media companies should rather sooner than later address the topic—both as a driver of public debate and in their organisations. On a systemic level, the loss of journalists harms a functioning democracy, and it's problematic yet understandable that many journalists switch to public relations and corporate communications.

Toxic Culture Impacts The Bottom Line

A toxic workplace is one of the biggest drivers of why people quit their jobs. "In today's competitive labour market, one of the leading reasons for high turnover is the emergence of a toxic atmosphere at work. Employees often leave bad workplace cultures in search of healthier environments, where they may feel more fulfilled on the job," writes The Society of Human Resources Management (SHRM).

There are five prevalent signs of a toxic culture in companies:

Why I Left The Media Industry After 10 Years

Since I was 15, I have wanted to become a journalist. Now, I say farewell to journalism, the industry that provided great experiences but also a lot of frustration.

Prologue

For years, if anyone asked me whether I could picture myself doing anything other than journalism, I categorically denied it.

Despite knowing that the media industry was a stressful environment undergoing a disruptive change, I still was intrigued by this industry in disruptive change. I wanted to become a part of that change and help shape the future of journalism.

However, after about a decade, I had enough. And although I had incredible opportunities, unforgettable moments, and great colleagues in every single company I worked for, the following post focuses on the negative that drove me out of the industry.

It's a highly subjective, personal, and biased account. Maybe a small reckoning.

Part I: Exciting Beginnings

My career as a journalist began as classic as possible. Never knowing what I should become, I signed up as a reporter for the school's newspaper because I had always had a passion for writing and storytelling. Then, it suddenly dawned on me that journalism is an actual job. I've found my calling.

But I was a lazy teenager and dropped out of school, starting an apprenticeship in 2009. Nevertheless, I had my goal and was eager to get a foot in the door. I started writing short band biographies for a concert photographer and freelanced for some webzines and a local paper. In 2010, I founded my magazine, Negative White, together with my brother, who had just bought his first camera.

These early years were shaped by curiosity, the excitement of the unknown, many mistakes and learning by doing. Most of the time, I didn't know what I was doing. But I had fun and could follow my passion. My magazine grew an audience and other volunteers. Two years in, I even had the opportunity to interview Sir Paul McCartney.

I became a member of the young media association, now called Junge Journalistinnen und Journalisten Schweiz (JJS), and began to grow my network. In 2013, I started studying journalism and communication. As part of the curriculum, I gained my first experience in editorial offices at the Swiss national broadcaster SRF and a local paper.

Part II: First Cracks

The internship at SRF was a wild ride with a committed team. I was never really interested in television, but I learned to love video content. And although I would stay at the news bulletin 10vor10 at the desk, the first cracks in my journalism dream started to show.

In hindsight, I had terrible tasks as an intern. It was the peak of ISIS, and I had to plough a whole day through propaganda material. Eight hours of beheadings, mass executions, and other glorified violence.

Working at the desk after the internship has been a thrill. Being part of live broadcast productions is an adrenaline-spilling affair. As a desk employee, I was the right hand of the producers, fact-checking, establishing connections to the correspondents, ensuring the correct timings of the lower thirds, writing online texts, and more—a great responsibility.

However, there was a lot of fluctuation in the team, which directly impacted the programme's quality. Often, the people at the desk were students, aspiring journalists who wanted to gain storytelling experience that they couldn't get at the job. So I drafted a proposal for the editor to allow us to create two stories a year. He declined and said: "This is a support job, and it will forever be one."

My encounter with the editor was the first that embodied an outdated management style characterised by a refusal to change, holding on to power, and sometimes unsettling behaviour.

As an online journalist, I still struggled with an older editor who told me we should do "more with boobs" online to boost clicks.

At the interview for my next job at another local paper, the editor-in-chief asked me about my political affiliation. After I dodged the question several times, he said: "If you had to choose to become a member of a political party or get stoned, which party would it be?" – I said: "I choose the stoning."

After being a journalist for a couple of years, I was less and less interested in writing about things I didn't really care about. I fully knew what I was getting into when I chose journalism as a career. It's a stressful job that makes it incredibly hard to have a proper work-life balance. Most companies don't have actual—and, by the way, legally required—time reporting. Instead, the system merely puts in standard daily hours to comply without accurately representing the work done. But many journalists I know have easily 100 hours of overtime.

The job also got more complex, requires more skills, but isn't that well-paid nor a highly regarded profession nowadays. Journalists used to have just one thing to do: tell the story. Today, you're expected to take photos, shoot videos, and post on social media.

In many regards, I've always been fascinated by these new facets. I saw it as an opportunity to learn new skills and maybe discover new areas I could excel. But there's no way around it: A lot of additional work is put onto journalists because fewer people are working in newsrooms.

However, I still felt that the media industry was an exciting field despite its dire situation with declining revenue. That's why I joined Blick, first as a Project Manager in the newsroom, later as Head of Community, and then as Product Owner. I hoped that switching to a more background position would keep me happy for a long time.

Part III: Only Management, No Leadership

"It's not a shitty job; it's the shitty conditions and perspectives," said Simon Schaffer of JJS recently. It's a brutally honest and accurate statement.

Especially freelance journalists are at the very bottom of the food chain: Karin Wenger, a friend and a freelance reporter covering the Middle East, tells me that she has to use a lot of her ever-smaller salary to cover travel expenses as most of the newsrooms scraped the budgets for things like travel and translators long time ago. It's madness.

I've written about mental health problems in the media industry before. However, I again experienced first-hand and by many accounts in the last few months how devastating the lack of leadership can be to people. I know many journalists who had burnout at around 30 [German] and had to get professional help. Or they even began abusing alcohol [German].

I regularly talk to talented reporters who feel similar: Yes, journalism is their calling. And yet, only a couple of years in, most of them are thinking about changing careers.

But who is ultimately responsible for working conditions that seem to make people sick or drive them out of their beloved field?

The management. And yes, I specifically use the term 'management' because there's a lack of true leadership in media companies. It's the main reason why I leave the media industry now.

I won't go into detail about my experiences in various companies. It's not about individuals or instances but a more systemic issue. A synthesis of my own accounts and those of friends or students at MAZ, where I used to teach, paint a clear picture: It all boils down to a lack of trust in the employees and a missing vision and strategy to align efforts.

- Safety over experimentation.

- Stop doing is rarely a sincere option.

- Great ideas get watered down through endless discussions.

- No strategic approach to 'shiny new things' like TikTok.

- Work done by internal teams gets challenged by expensive external agencies.

- Reports are created for accountability rather than an opportunity to learn.

- Expertise is less important than gut feeling.

At some points, I was amidst internal political struggles and personal agendas, but I had no interest in participating. It's wasting time and energy.

Leadership should provide an environment that empowers people and allows them to be at their natural best. And if a company hires, for example, an UI/UX designer, you should probably listen to their advice. Otherwise, why did you hire them in the first place? However, from my experience and what I regularly hear from friends and colleagues, micro-management is prevalent.

I fully recognise that the media industry is in a dire situation. Revenue is shrinking, and although alternative business models exist, there's no one-size-fits-all solution. The broader media and information landscape has constantly been disrupted for decades by new technologies and platforms. Change is a constant, requiring a new kind of leadership mindset, organisational structure, and corporate culture. But frankly, media companies are still managed like 30 years ago.

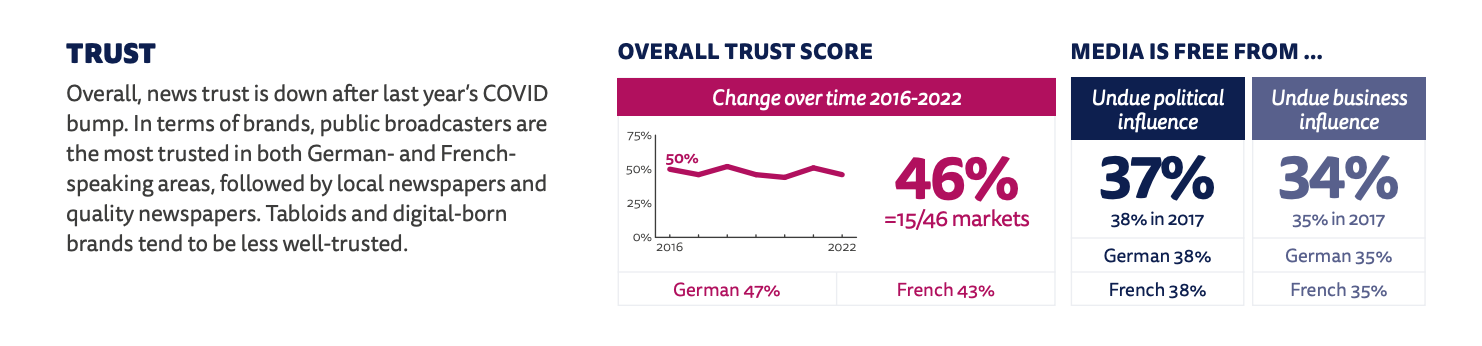

The declining trust in journalistic work is a fundamental challenge for the industry. And I began to realise that if an organisation cannot create that trust within itself, it's probably futile to build it towards the institution.

Epilogue

After only a bit more than four years, I decided to leave Blick. I was disillusioned, frustrated by the media industry, and physically and psychically exhausted. In the mornings, I was almost unable to get out of bed. I didn't feel any joy because I couldn't do my job properly. I felt an impending burnout.

I was done fighting, especially after having already spent a lot of energy to get recognised with the Community team I helped build. Despite working alongside hugely talented and committed people, I felt that I couldn't give enough anymore that I was satisfied with myself. It's a sad realisation, yet it also gave me a weird sense of calmness.

With just three bigger media companies left (two of them I've already experienced), I only wanted to get out of the industry I worked hard to get into years ago. And I'm glad I'm out because it began eroding my passion for writing and journalism.

Employee retention is another challenge closely connected to the company culture and trust. It gets harder and harder to find interns, and a quick check of medienjobs.ch reveals that attractive offerings remain open for months. When looking for my first full-time job, I hardly saw any open positions.

Last year, every week, a journalist left the field in Switzerland. The media magazine persoenlich.com is running a series of interviews with former journalists. So it should be an eery wake-up call for all brands and the industry that there's a problem. Simon Sinek said it perfectly:

"The Great Resignation is an indictment on decades of substandard corporate culture and poor leadership."

Being a journalist has been and will always be an exciting profession. But today's ecosystem is failing the people and employees. Maybe these big legacy brands need to vanish and make space for something new if they're unwilling to fundamentally change how they do business. I certainly will miss journalism but not the system that produces it today.

A Personal Note

I'll join Zeilenwerk as a Product Owner in August. After about a decade, I will leave the media industry.

Some of you might have already read that I will soon leave Blick. Today, I can announce that I will join the Swiss software agency Zeilenwerk as a Product Owner in August.

I look forward to collaborating with a purpose-driven team on sustainable solutions for our customers.

It's a big step since I've been in journalism/media for about a decade. It's what I know. The decision to switch not only the industry but also the work environment—from a big and relatively stable organisation to a smaller and nimble company—wasn't easy for me. I expect the cultural shock will hit hard.

However, I believe change is always an opportunity. And leaving one's comfort zone encourages personal growth. I also felt a strong connection to Zeilenwerk's culture centred around mindfulness. Aside from projects, it's a vital part of Zeilenwerk that everybody can shape the company, from self-organisation to self-set salaries.

Oh, and Zeilenwerk is currently looking for new developers. So if you know anyone who might be interested, please forward them to the open positions here.

I plan to write a longer post about why I leave journalism behind. As for this small newsletter: I'll continue to write about leadership, collaboration, and digitalisation, but probably much less through the lens of the media industry.

Nevertheless, I hope you'll stick around anyway.

Rethinking Office Days

In the wake of the pandemic, companies have started to embrace work from home. But they rarely rethink office days.

Last week, Airbnb's CEO Brian Chesky announced the company's new remote work design. The fundamentals are the following:

- You can work from home or the office

- You can move anywhere in the country you work in and your compensation won’t change

- You have the flexibility to travel and work around the world

- We’ll meet up regularly for gatherings

- We’ll continue to work in a highly coordinated way

On the surface, Airbnb's announcement isn't any different from what other companies have introduced in the wake of the pandemic. Working from home (or anywhere) has been part of many lives. And while it's a question of individual preference, there's no denying that the ability to choose your workplace is appreciated.

The work from home generation is about to shift how we organise office policies and design spaces and how our homes are built.

There Is No Blueprint Solution

It seems pretty straightforward for those who crave more flexibility in organising our daily work: Just give me the maximum of freedom. Unfortunately, however, most companies are complex organisations, and some people may have roles which don't allow them to work from home for any number of reasons.

The Metaworse

Let's take a look beyond the marketing hype.

I've been creating digital avatars for the better part of my life. It was probably not the first one, but the one I clearly remember: my alter ego in the MMO Guild Wars around 2005. Later for Star Wars Galaxies and Star Citizen.

Being fascinated by the immersive nature of games, I fully understand the notion of re-creating oneself in a digital world, joining people from around the world and going on adventures.

For me, born in 1990, the internet and digital spaces have been a welcome escape from Switzerland's conservative and boring countryside. And some of my oldest friendships trace back to those intense gaming times, although they trickled into "real life" now.

I also strolled around in Second Life for those who can remember the first actual attempt to re-create the world in the digital realm. However, when I tried the simulation, the initial hype had already passed, and the concept didn't capture my mind. The main problem: Second Life was like real life. Everything cost "Linden dollars", which could be purchased for actual dollars, diluting my escapist desire.

In 2015, I first put on a VR headset. It was an Oculus Rift Development Kit II, even before the company formerly known as Facebook bought the enterprise.

Since then, VR technology has come far. First, the resolution and general experience improved to make virtual reality access consumer-ready. Combined with the astonishing progress in video game graphics, a second attempt at creating a metaverse seems inevitable.

Given my previous gaming experience and general affinity for technology, I should be excited about the current efforts around the metaverse. But I'm not.

What Is The Idea Behind The Metaverse?

"The metaverse is defined as a unified 3D virtual world where users can conglomerate via their digital selves (i.e., avatars) and perform complex interactions," writes XR Today. It's pretty vague, to say the least.

But the hype is real. Billions are invested in creating the technological foundation for the metaverse. Most famously, Facebook announced its move with a silly rebrand into Meta. But also Epic Games (the makers of Fortnite and the Unreal Engine), Chinese tech giant Tencent, Microsoft, and even Apple are working on it.

Despite its vague definition, I have little doubt that the companies involved in building the metaverse have the financial resources and technological capabilities to create an excellent experience.

Fragmented Domains

Meta's CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, stated in his manifesto: "When you buy something or create something, your items will be useful in a lot of contexts, and you're not going to be locked into one world or platform."

Public perception of the metaverse is precisely that: People and companies pouring metric tons of marketing money into the idea are expecting a single platform. And Meta repeatedly said that no single company would own the metaverse.

I call bullshit.

Culture of Speed

Why the culture of speed makes it hard for newsrooms to embrace a product mindset.

The business of news is fast-paced. New information surfaces faster than ever before; bulletins, press releases, and tweets drop in by the second. For the past years, newsrooms had to adapt to process the ever-faster spinning news cycles, verifying and curating the most important and relevant information for their audiences.

The traditional deadline approach from print times has been largely abandoned in the digital publishing realm. Instead, stories get published throughout the day to meet the demand. Then, journalists move on quickly to a follow-up or even a new story.

The increased pace creates many challenges around journalism itself worth exploring. However, this culture of speed established in newsrooms also makes it difficult for media organisations to embrace the transformation to a product-focused mindset fully.

Agility On Steroids

People working in product management—including myself—tend to complain about the newsroom's lack of understanding of agile development. There are undoubtedly true aspects to this.

Usually, a story is refined until published; changes occur rather occasionally than institutionalised. The journalists' strive to perfection, paired with a still roaming deadline socialisation, is fundamentally different from an iterative approach to product development.

But the more I think about it, the less confident I am in this theory that a lack of knowledge is why news organisations struggle with a product mindset. There are two key reasons:

- The production of journalism is in itself an agile process. Like any product, stories go through discovery (research, investigation) and delivery (writing, production) phases. Each draft is a prototype that is being re-iterated based on new information and feedback.

- Newsrooms are masters in agility. No organisation outside of journalism can react as quickly to new developments as newsrooms. In case of breaking news, priorities are shifted dramatically in a matter of minutes. Everyone that has experienced a breaking news situation for the first time is stunned by the impressive adaption rate.

Basically, newsrooms live agility on steroids. They move as fast as the news cycle requires.

Note

This observation is only valid for highly digital, news-driven organisations. Local newspapers still relying heavily on print indeed struggle with agility, while more magazine-like online publications have a much slower pace.

Understanding Cultural Differences

If we leave assumptions and biases aside, we can assess that both the newsroom and the product development work agilely—the main difference is the speed. Additionally, every organisation has a third gear that moves even slower: Strategy. It's even more complex to translate to everyday work in a newsroom than product development; strategy plays hardly any role in deciding which stories to write. On the other hand, strategy is a massive factor in a product roadmap.

Update

Of course, strategy plays a significant role in the editorial direction of a news organisation. However, in journalists' daily work, it isn't as prevalent as it is for product management.

Nevertheless, understanding that the newsroom and product development basically work with the same principles but at different speeds is crucial. It creates a common ground for communication and education, which drive culture change.

As a product manager in a media organisation, it is essential to be aware of the culture of speed inside the newsroom. Furthermore, he has to thoroughly understand how the journalists work on their part of the product. These two factors heavily influence the interactions between newsroom and product to happen.

The culture of speed often leads to exaggerated expectations. "We need feature X now!" or "Why does feature Y take so long?" are phrases you‘ll often come by in discussions with newsroom staff. The constant urgency is deeply engrained into journalists' mindsets and drives their behaviour in every interaction. As a journalist turned product manager, I still feel this need for speed.

Attach Communication To Familiarity

If a product manager has no or little knowledge of the cultural background of these phrases, it gets difficult to find satisfying answers. So, an effective way is to find familiarity in comparisons between journalism and development.

Here are some examples:

- Product development is like investigative reporting. You need time and teamwork to get to the bottom of the user story.

- The roadmap is like an editorial publication schedule. Priorities can change like news cycles, but they usually shift not so fast.

- User-centred development is like optimising a headline. We want to deliver a product that captivates the audiences and keeps them engaged.

You can develop many other comparisons to create a common language and start educating effectively.

Don't Neglect The Differences Either

Naturally, it is not the solution to bridge every difference. Communicating that the differences aren't as big isn't enough. Education still needs to take place.

Product development has more constraints and stakeholders that need consideration, whereas journalists (in an ideal world) only are bound by their principles and only answer to the audience.

Furthermore, product iterations usually have larger leverage and more considerable risk. In comparison, the newsroom speeds through dozens, even hundreds of iterations with every published story, the individual article itself has a much lower impact. Suppose it performs well, great! If it doesn't, it's soon forgotten. There's no lasting impact on the product.

Note

Obviously, journalism can have a great impact on society and policy or the product and brand perception. While an individual story may trigger an impact on the first two, it's far more unlikely that a single story changes how the product or brand is perceived.

However, if there's a product change, it may instantly impact everything—from the user experience to advertising performance. And these changes cannot easily be reverted like a typo in a text. Research, consideration, and alignment must be thorough as the danger of significant impact loom above every feature change. It takes more time.

Best Of Both Worlds

Now, both the immense speed of the newsroom and the slower tempo of product development have their righteous existence. They're needed to create success in their respective fields, and pitting one speed against the other isn't a good idea.

However, to see progress within the shift to a product-driven organisation, we have to think about how we can bring both worlds together and even learn from each other. The questions around effective collaboration can be:

- What can product managers learn from the speed of the newsroom? And vice versa?

- What strategic goals can be translated to product and editorial to enable a department-spanning collaboration?

- Which opportunities provide the best area to grow from each other's strengths?

Ultimately, only joint forces between all departments in the organisation leads to an effective transformation process.

My Spotify Dilemma: The Power of Product

I hate the company but love their product.

My journey into journalism started back in 2007 when I began writing for the school newspaper. Soon after, I collaborated with a photographer and wrote short biographies about the artists he photographed. It was my start in music journalism.

Back then, music streaming was a thing of the future. Peer-to-peer networks like Limewire were one sketchy source for my iPod library, managed on iTunes. I imported CDs from my uncle's vast collection to extend my musical horizon. And I often bought the silver discs at shops and concerts, only to digitise them shortly the next day.

Later, while working on Negative White, the online music magazine I ran for a decade, iTunes was still a vital part of my music consumption. I could add promotional CDs and digital downloads before the release date.

Coming from the iPod and iTunes experience, I soon pivoted to Apple Music as a streaming service; however, I mainly stuck to my own digital library. And I didn't intend to switch to Spotify, mainly because I read all the stories about how little artists earn on the platform.

I can't remember the exact moment–or even the reason for that matter–why I switched from Apple Music to Spotify. But it only made sense: The service gained more traction and influence, alongside the album's downfall and the rise of playlists–the new tastemakers. As a music journalist, I had to be where the magic happened. I had to provide playlists where the audience was.

And I never questioned my move to Spotify again. Then came 2022.

Young vs. Spotify

For those who don't already know what I'm going to talk about: Here's a quick and dirty wrap-up.

Neil Young attacked Spotify for being a platform for misinformation around Covid-19. "I am doing this because Spotify is spreading fake information about vaccines — potentially causing death to those who believe the disinformation being spread by them," he wrote in a now-deleted open letter.

The main reason for Young's anger: podcast host Joe Rogan. In 2020, Spotify struck an exclusive deal with possibly the world's most prominent podcaster. Estimated worth: more than $200 million, as the New York Times lately reported.

However, Rogan regularly delivered controversies around the coronavirus. For example, he took Ivermectin, the infamous horse dewormer, when he contracted the virus. Rogan also was criticised for hosting Robert Malone, a popular figure in the anti-vax movement.

Although Young's fame puts a bigger spotlight on the topic, he wasn't the first to address the issues around Rogan. For example, 270 doctors signed an open letter to Spotify after Malone appeared on Rogan's show.

"Why did Spotify choose Joe Rogan over Neil Young? Hint: It's not a music company."

The preliminary result of Young's protest: Spotify did as he wished and removed his music from the platform. But also, other artists like Joni Mitchell joined Young's cause.

It may seem weird that a music streaming service quickly chose this route. But the Washington Post explains it already clearly in a headline: "Why did Spotify choose Joe Rogan over Neil Young? Hint: It's not a music company." The article highlights Spotify's heavy investment into podcasts and its strained relationship with artists.

Ethical Questions

Since all this went down, the ongoing debate made me think about my relationship with Spotify as a company, as a product, and more generally, about how I consume, enjoy, and value music.

I still maintain an extensive physical collection of CDs and vinyl. And the digital library counts over 30'000 songs that no company can arbitrarily remove. It weirdly comforts me.

And after I learned about Spotify CEO Daniel Ek's €100M investment in defense AI, I had to confront myself with the question: Do I want to contribute to all of this?

Do I want to have a relationship with a company whose primary purpose seems to aggregate data and somehow manage to make us love being spied on—even so far that it can predict our moods?

Do I want to spend money for a service that pays the artists virtually nothing, doesn't take responsibility as a publisher (which Spotify became with its big move into podcasts and Joe Rogan), and doesn't seem to care about their own codes?

Good Intentions

I inherently believe that many of the questions above have to be tackled on a societal level. Spotify is finally seen alongside other platforms like Facebook, Instagram, Substack, and YouTube. We as a society have to conclude how we deal with those platforms and their impact on our lives, communities, and information ecosystem.

However, I, too, have to take responsibility. As a music curator (check out Weekly5 if you're interested), I use Spotify not only privately but also somewhat professionally. So I decided to take action and pledged to buy every song I feature on Bandcamp if it's available. Subscribers can verify it by checking my profile.

And finally, I started to use Apple Music again as a primary streaming service. Here's where the dilemma began to unravel.

The Better Product

I immensely appreciate one particular aspect of Apple Music: the quality is quite frankly astounding. I didn't think that Apple's Lossless format would make such a difference.

Another positive side of Apple Music: I can combine my existing digital collection with the streaming offering. But that's about it for the good things.

I attempted to use Apple Music the same way I use Spotify: Find songs, curate my playlists and listen to them. I don't listen to existing playlists aside from occasionally skipping through Spotify's personalised mix and checking the "Release Radar" every Friday to see if I find something for my Weekly5 curation.

Now, let me illustrate my struggle with Apple Music compared to Spotify with five concrete examples. (Disclaimer: There are far better design reviews out there like this one, this is simply my personal experience.)

2021 Reflection

Looking back and ahead.

2021 is about to end, finally. It’s been a tough year, full of changes, uncertainty, and turmoil, but also bright highlights and precious moments. A year that felt like a decade’s worth of experiences.

And now, it’s time to look back and reflect on the past months, the excellent parts and the rough patches. But it’s also the time to look ahead. For this reflection, I use a personalised version of the End of Year Reflection by Hyper Island. I can only recommend doing a reflection yourself.